Table of Contents

Introduction

A sustainable and smart health system is crucial for all Australians since it allows for the population to make lifestyle choices that are better and reducing the occurrence of the devastating chronic diseases. This system would enable the Australians to have greater control over access to health services and their care. In so doing, will manage to adopt new services like remote monitoring, eConsultations, enhanced health data access and scores of other benefits associated with digital revolution. In the last few years, Australia has implemented a number of significant initiatives with the goal of enhancing the performance of the country’s health system. This can be evidenced by the reforms carried out between 2010 and 2012 by the Federal Government, which includes the introduction of National Partnership Agreements and activity-based funding. Besides that, the territories and states have rationalised to the local level their centralised devolved funding and health bureaucracies, delivery and planning responsibilities. Although the reform efforts were significant, they were insufficient in ensuring that the Australia’s health system will in the future become sustainable. The health services cost is increasing at twice the GDP rate. Burgeoning health expenditure is an issue that is exceedingly challenging to solve due to many factors that drives the health costs up, and the majority of them are deeply rooted in the complex health system. Irrespective of the challenges, the Australian government has tried to use numerous policy tools to control the growing health care expenditure. The objective of this piece is to discuss how health expenditure could be controlled with particular reference to current policy debates on health expenditure.

Discussion

According to Kemp, Preen, Glover, Semmens, and Roughead (2011), Australian patients have continuously been facing increasing costs of prescription medicines and the spending per patient is currently between the middle and upper range with corresponding nations. The increasing costs of medicine have significantly influenced the use of and access to prescribed medicines; thus, leading to the increase of risks related to patient well-being and health. For that reason, it has become imperative for the policymakers to consider the on-going medicine affordability to the wider community when going through pharmaceutical reimbursement policy. As mentioned by Davey (2017), Australia health expenditure in 2016 was $170.4bn, which is more than 10% of GDP. Australian health finance’s key problem is related to the divided responsibilities of state and federal governments. Despite having too many costs, the states have few financial resources while the federal government’s responsibility to pay for medical services by means of Medicare have resulted in silos between the health system’s key parts. This has led to cost shifting blame game, particularly with regard to ensuring transparency in the hospital expenditure. This led to the introduction of Activity-based funding (ABF), whereby the hospitals are paid a standard price for the delivered services with the goal of promoting greater efficiency. According to Gillespie (2013), ABF was promising since it slowly but surely increased the share of Commonwealth in hospital funding. The health reforms steered by Council of Australian Governments (COAG) focused on the hospitals, especially the emergency waiting times and elective surgery queues. Enormous efficiency gains can be achieved by enhancing the capability of diverse parts of health to allow for seamless interaction. Gillespie (2013) posits that medical services payments under the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) and pharmaceutical benefits scheme are the main part (approximately 60%) of Commonwealth health expenditure. A report by Committee for the Economic Development of Australia established that the federal government can make major savings if they bargain harder over the prices of off-patent drugs (Gillespie, 2013). As mentioned by Bennett (2013), Australia has started strengthening its primary health care as evidenced by the establishment of 61 Medicare Locals, which support preventive action at the local level.

In 2011–2012 Australia’s health expenditure (AU$140.2 billion), the government funded 70 per cent of the expenditure while the patients and private health insurers paid 17% and 8%, respectively (AIHW, 2014). Estimation by the Grattan Institute, as cited by Gillespie (2013), indicates that the federal government can save approximately A$1 billion through better pricing policies. Prevention and incentives are two areas of Australia’s health system that have largely been misaligned. Prevention has largely been neglected considering that chronic illnesses related to lifestyle, like diabetes, have become a major burden on Australia’s health system. On the other hand, incentives for Australians to become responsible for maintaining their health have hardly changed. The split between primary health care and hospital funding have resulted in obstacles to communication and cooperation between health-care providers. Until now, health expenditure consumes an increasingly large percentage of federal and state budgets. A number of expenditure categories are more expensive as compare to others, particularly pharmaceuticals, hospitals, and primary care (which includes Medicare). The high costs are attributed to a number of factors such as ageing population and high population growth rate. Besides that, health inflation is increasing faster as compared to the Consumer Price Index. The major factor that contributes to high health expenditure is attributed to the fact that medical services per person are exceedingly expensive and are accessed more frequently. Technology advancement has improved the quality of treatment; thus, patients are receiving medications or treatments which were non-existent a decade ago. For instance, an average 60-year old go to the hospital receives more medications and treatments more frequently than a typical 60-year-old did 10 years ago. The increasing access to medical services is the main reason why Australia is experiencing high health expenditure. Although Australia has an impressive standard of health care than other developed countries because of advanced health systems, these advancements are very costly.

Controlling the Costs

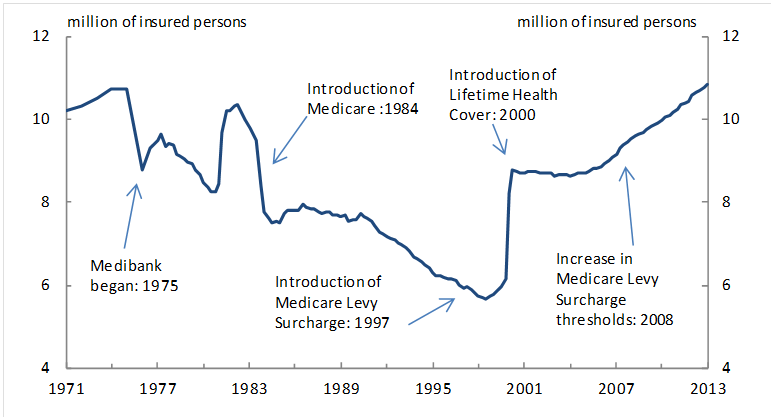

According to Budget Direct (2017), prevention will always be better than cure; therefore, when Australians keep themselves healthy, the government would be able to beat the ballooning health expenditure. Reducing the need to access health services, will help government spend less from year to year. Lifestyle-related diseases contributed largely to the country’s burden on the health system. Having healthy lifestyles can help the government make enormous savings in relation to health expenditures. According to Lehane (2014), health can be influenced by a number of social influences such as lifestyle and behavioural factors (unemployment and social factors). Besides that, private health insurance (PHI) can help lessen the financial pressures related to the unforeseen health calamities such as being admitted in the hospital, inability to work because of injury and different other unkind surprises. The insurance can help the Australians maintain health by paying for specialist medical services such as optometrists, physiotherapists, chiropractors, dentists, and others. According to NCOA (2014), the higher-income earners should stop using Medicare for basic health services, but instead, take out PHI. All Australians can access universal health care thanks to Medicare but this comes at a significant cost since the limited resources from people who need the health care more are diverted to those that do not. Therefore, effective Medicare targeting would help protect people who are truly disadvantaged. That is to say, Commonwealth should reduce the amount of subsidies it offers to people who can fund their own health care. NCOA (2014) suggest that Australians with higher incomes should take responsibility for their health care cost since they are well positioned to take out PHI. It is imperative that they stop depending on government funding. Besides that, the health insurance coverage offered by the private companies should be expanded to accommodate basic health services, which is covered currently by Medicare. Figure 1 shows Australia’s hospital treatment coverage through PHI.

Figure 1: Number of People using private insurance to get treatment (between 1971 and 2013) (NCOA, 2014)

Co-payments

Another way of controlling high health care expenditure, according to NCOA (2014) is co-payments, whereby the consumers are required to make a small contribution towards the payment of their health care costs. Basically, co-payments would send a clear price signal to all Australians that the medical services they frequently access come at a significant cost. In so doing, the demand for overused or unnecessary medical services would be reduced, and Australians would be encouraged to take responsibility in paying for some of the cost associated with their health care decisions. In this case, the co-payment can be anchored in the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) structure, the matrix pricing structure. In this case, the co-payments focus on the simple means test rooted in concession status and supplemented through a reinforced safety net arrangement. The Chronically Ill and lower-income earners would be protected from high out-of-pocket costs by implementing the safety net when the patient surpasses 15 visits in a year. After exceeding the safety net threshold, the patient’s co-payment could be reduced by half. For emergency rooms, the co-payment structure could be anchored in the hospital triage categorisation system. Currently, the emergency room patients are triaged based on the medical attention urgency; conditions that are life-threatening, critical, or potentially life-threatening are grouped in triage categories one to three while less-urgent conditions are related to triage categories four and five. Therefore, co-payments for triage categories four and five should be introduced by the state governments.

According to Richardson (2014), co-payments are viable ways of controlling total costs, but their effect is very small. Co-payments divert patients towards higher-cost outpatient care since most people are inclined to defer the needed treatment but eventually would need more expensive specialist care. Eliminating bulk-billing would likely increase GP expenditures and fees through reduction of competitive pressures. Therefore, increasing co-payment from $7 to $10 would likely affect the GP practice adversely as compared to the bulk-billing cessation as well as the initial co-payment introduction. Inflating fees could be accelerated when the Australian government capitulates to the pressure of allowing the PHI to cover the gap that is still widening. Richardson (2014) holds that increasing the GP fees could become more desirable considering the low GP incomes level. Still, a remedy that is more equitable would be to increase the rebate rather than decreasing it.

Recently, a number of cost control strategies, as cited by Rickard (2002), have been proposed; increasing patient co-payment and reducing subsidised access to ‘non-essential’ drugs. According to Rickard (2002), increasing co-payments is certainly the most direct way of reducing costs associated with the PBS. Increasing the co-payments for concessional and general patients can lead to enormous cost savings, but they are likely to pose a serious burden on some Australians, especially amongst the low-income earners. Increasing co-payments could lead to failure amongst the patients to fulfil their scripts, which consequently could result in a major risk of deferred costs of health care, which would ultimately affect other areas of the health care system. The high health care expenditure can also be controlled by reducing subsidised access to drugs deemed to be non-essential. Numerous subsidised products such as anti-fungal medicines, anti-inflammatory products and some nasal sprays have been de-listed to cut costs. Most of the de-listed products were used for treating common or minor conditions. The relevant Budget statements, in numerous instances, pointed out that the PBS funds could be spent effectively in treating more serious illnesses.

Medicare, as pointed out by ANMF (2015), is the most effective way of funding health care, especially in contrast to PHI. The PHI administrative costs, in addition to the profit margin, are approximately threefold that of Medicare considering that Australians pay almost $2.5 billion annually toward such costs. For every dollar collected by the private insurers in Australia, only 84 cents is returned as benefits while the remaining account for the corporate profits and administrative costs. On the other hand, 94 cents is returned by Medicare returns for every dollar collected. Despite enhancing health care access in Australia, Medicare has some cracks. The majority of Australians are served adequately but access and outcomes-related inequities have started manifesting. According to ANMF (2015), improving Medicare and its coverage is the only way of sustaining the health spending. Health care access amongst the disadvantaged should be enhanced while the role of private insurance should be contained.

Integrated Funding

According to Bartlett, Butler, and Haines (2016), public funding fragmentation is one of the residual challenges for enhancing the supply of health system. Although Australia has made some steps in the right direction by introducing activity-based funding to replace historical public health services funding and devolving public health funding to catchment areas, the country is yet to develop rational long-term service plans that rationally align the health resources to latent and actual health demand. The fragmented public funding makes it impossible to control high health care expenditure and makes the health system fundamentally sub-optimised and inefficient. Basically, devolving funding and responsibility to local hospitals would enable the country to move in the right direction since responsive and flexible consumer-focused and locally managed health services are inclined to generate efficiency and effectiveness dividends.

Optimising the Care Pathways

As mentioned by Bartlett, Butler, and Haines (2016), understanding as well as managing the health system’s demand flow and making sure that the care setting mix in the catchment areas is matched optimally to projected demand is very imperative. Basically, optimisation of the care setting mix in the health catchment areas plays a crucial role in ensuring that the right care is provided at the right place in a timely manner. This can be achieved by investing in the improved capacity in several types of care setting, for instance, home care and sub-acute.] Cross-care setting pathways would offer a crucial input to an integrated and more rational health services funding in the catchment areas. Bartlett, Butler, and Haines (2016) posit that identification of ideal stay durations for all types of care setting type during the illness episodes for certain conditions could be utilised in calculating the suitable types of care setting mix needed to meet present and forecasted demand in the catchment areas. Basically, the emphasis on illness episodes instead of episodes of care and integrated care pathways in the cross-care setting would need changes to available care models to allow for the accommodation of the cross-care and broader setting imperative.

Encouraging competition

According to Boxall (2011), competition is not only a key driver of innovation but also efficiency. Competition is limited in a number of areas in the Australian health system. To effectively design and implement health care, competition policies, the policymakers should first understand that health care is completely different from other markets. The government should encourage greater role substitution, like using physicians’ assistants or nurse practitioners where appropriate. The process of training medical specialists should be made more transparent. The Australian government should resolve the long-standing questions regarding the role of PHI in the Medicare context. Managed competition should be promoted between insurance funds through reallocation of the existing public subsidies for PHI to other areas like bed subsidies in private hospitals or paying the public hospitals directly. As mentioned by Duckett and Breadon (2014), hospitals should provide data that show which expenditure can be avoided and where that expenditure is concentrated. In so doing, it would become easier for hospitals to identify the areas that need improvements. The management of the public hospital system should concentrate on avoidable cost. The Commonwealth Government, according to Burgan (2015), utilises numerous measures to encourage Australians to participate in PHI. Basically, these measures consist of Lifetime Health Cover, the Federal Government Rebate’s ‘carrots’, as well as the ‘stick’ of the Medicare Levy Surcharge.

Basically, access to health technologies, like medical procedures, diagnostic tests, medicines, medical devices, and others have offered substantial benefits to Australians. These technologies, however, come at a cost, and they are the main contributor to the inflating health expenditure. In this case, Productivity Commission (2015) suggested that evidence-based evaluation of existing and new health technologies can help deliver health care that is clinically cost-effective. The Health technology assessment (HTA), proposed by Productivity Commission (2015), is a system of institutions as well as processes which utilise scientific evidence in examining the cost-effectiveness, safety and quality of health technologies. More importantly, HTA informs decisions by the government regarding public spending on health-related services and products. Roundtable participants in Productivity Commission (2015) study suggested that PBS and MBS should be reviewed and disinvestment processes should be enhanced. Although the government commitment to reviewing the available MBS items was a crucial step towards the right direction, only less than 10 reviews have been carried out between 2010 and 2015. This demonstrates the inadequacy of these arrangements. To overcome this inadequacy, the MBS review work should be expanded and accelerated with reinforced transparency and accountability requirements.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this piece has discussed how health expenditure could be controlled with particular reference to current policy debates on health expenditure. Some of the measures that can help control health care expenditure in a continuous manner include evidence-based evaluation of existing and new health technologies, encouraging competition, optimising the care pathways, co-payments, integrated funding, and encouraging higher-income earners to take out PHI. Clearly, enhancing the Australia’s health system sustainability is a daunting due to the major challenges related to fragmented public funding, inequity, and many others. In contrast to other countries, the Australian health system is undoubtedly effective and efficient and effective. However, this has been made possible by the ballooning health care spending, which poses a serious issue with regard to future fiscal sustainability. Clearly, reducing the health care spending needs a holistic approach such as considering health services’ demand and supply and enhancing the way through which the health system’s elements interact with each other. The burden of escalating chronic disease, sedentary lifestyles and the ageing population has increased the demands on Australia’s health system. Although the cost of Australian health system presently represents more than 10% of GDP, the federal government’s health expenditure per individual would likely double in the next four decades unless the government starts thinking differently regarding health care. Basically, the revived agenda for national health reform should effectively handle the available complexities in Australia’s health system. The administration responsibilities and funding between diverse government layers should be fragmented. The reforms should as well involve all stakeholders, which include pharmaceutical companies, insurers, private hospitals, fitness and nutrition players, technology suppliers, research institutions, and many others.

- (2014). Australia’s health system. Retrieved from Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: http://www.aihw.gov.au/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=60129547593

- (2015). The facts on Australia’s health spending. Retrieved from Australian Nursing & Midwifery Federation: http://anmf.org.au/pages/the-facts-on-australias-health-spending

- Bartlett, C., Butler, S., & Haines, L. (2016, May 2). Reimagining health reform in Australia: Taking a systems approach to health and wellness. Retrieved from Strategy&: https://www.strategyand.pwc.com/reports/health-reform-australia

- Bennett, C. C. (2013). Are we there yet? A journey of health reform in Australia. The Medical Journal of Australia, 199(4), 251-255.

- Boxall, A.-m. (2011, November 18). What are we doing to ensure the sustainability of the health system? Retrieved from Parliament of Australia: https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1112/12rp04

- Budget Direct. (2017). Budgeting For Health Means Making The Right Choices. Retrieved from Budget Direct: https://www.budgetdirect.com.au/blog/the-rising-cost-of-australian-health-care.html

- Burgan, B. (2015). Funding a viable and effective health sector in Australia. The University of Adelaide. Adelaide: Australian Workplace Innovation and Social Research Centre.

- Davey, M. (2017, October 5). Australia’s healthcare spending rises above 10% of GDP for first time . Retrieved from The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2017/oct/06/australias-healthcare-spending-rises-above-10-of-gdp-for-first-time

- Duckett, S., & Breadon, P. (2014). Controlling costly care: a billion-dollar hospital opportunity. Melbourne: Grattan Institute.

- Gillespie, J. (2013, December 15). Securing Australia’s future: health care. Retrieved from The Conversation: http://theconversation.com/securing-australias-future-health-care-19765

- Kemp, A., Preen, D. B., Glover, J., Semmens, J., & Roughead, E. E. (2011). How much do we spend on prescription medicines? Out-of-pocket costs for patients in Australia and other OECD countries. Australian Health Review, 35, 341–349.

- Lehane, L. (2014). Illness, Poverty, and Abuse of Migrants on the Thai-Burma Border: The Vulnerability of a Displaced People. New York: Edwin Mellen Press.

- (2014, February ). A pathway to reforming health care. Retrieved from National Commission of Audit: http://www.ncoa.gov.au/report/appendix-vol-1/9-3-pathway-to-reforming-health-care.html

- Productivity Commission. (2015). Efficiency in Health. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Richardson, J. R. (2014). Can we sustain health spending? The Medical Journal of Australia, 200(11), 629-631.

- Rickard, M. (2002, May 28). The Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme: Options for Cost Control. Retrieved from Parliament of Australia: https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/Publications_Archive/CIB/cib0102/02CIB12